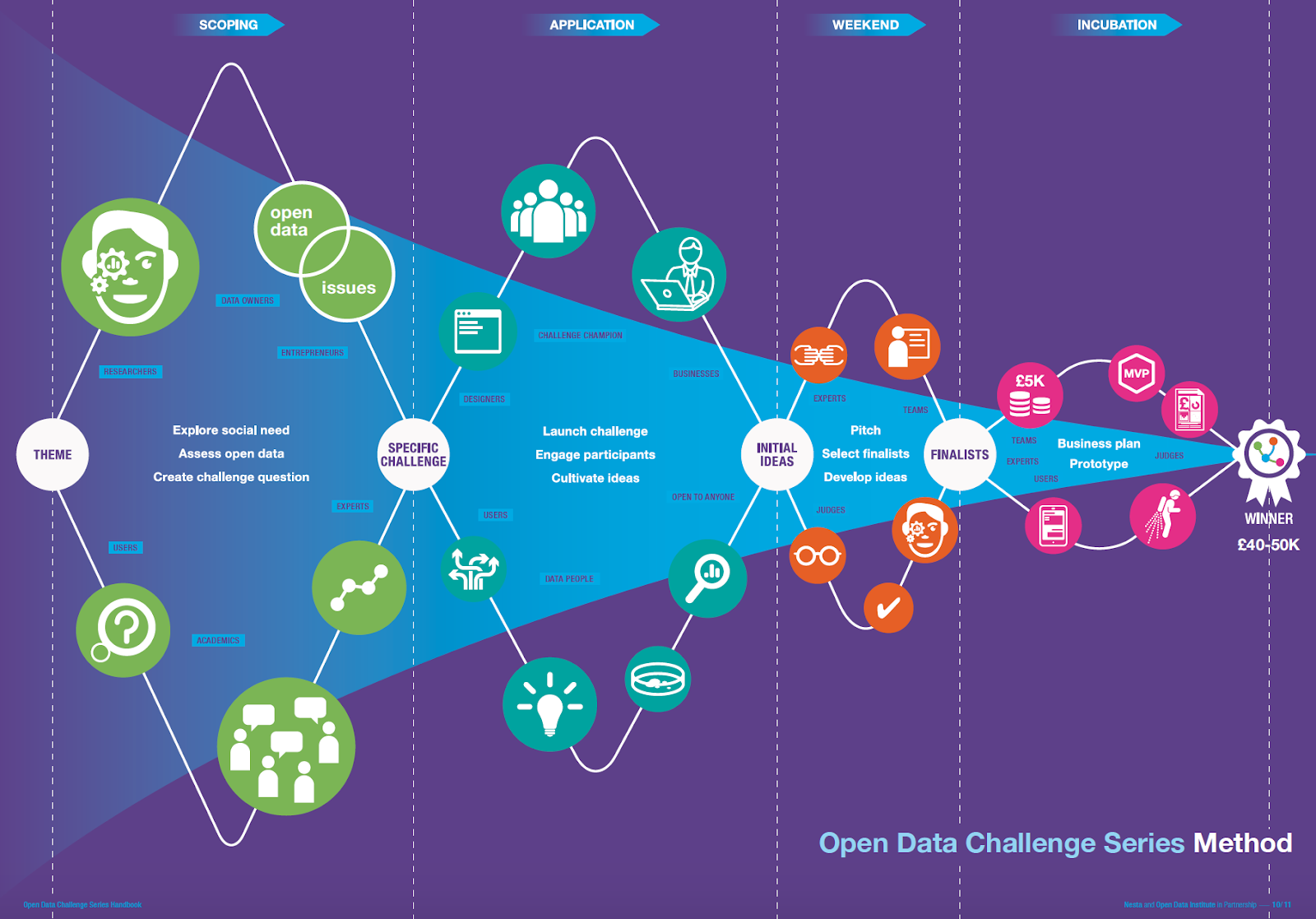

Whether your Citizen Observatory is looking to fully sustain itself or to promote targeted innovation activities, there are opportunities to encourage the uptake and use of Citizen Observatory data by industry and SMEs. Initiatives such as an Open Data Challenge (ODC) can demonstrate how data acquired within Citizen Observatory can help private sector businesses address data needs and gaps.

The purpose of this activity is not primarily to engage a large number of people, but rather to create a number of sample applications that might:

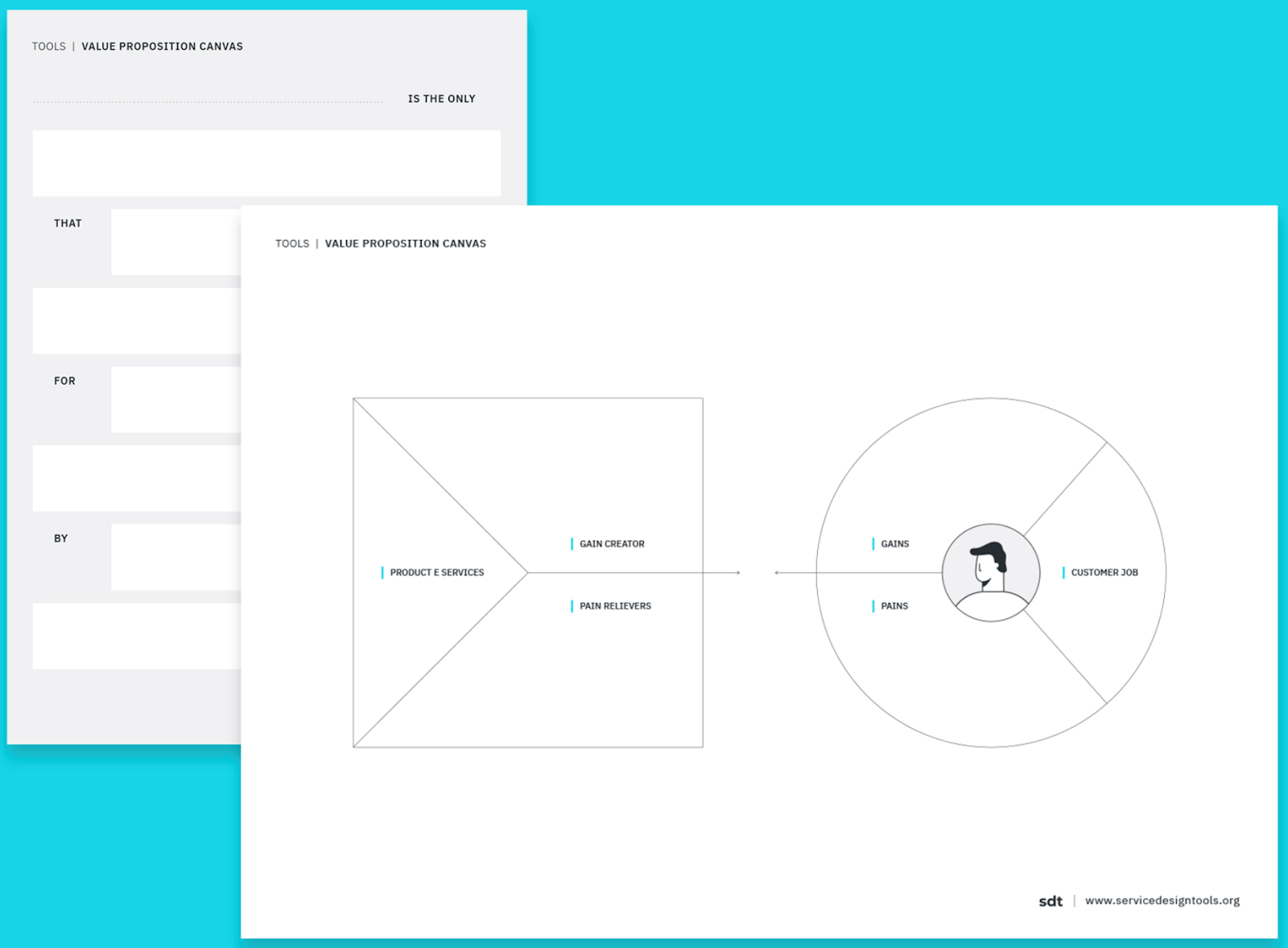

Planning an Open Data Challenge from the Nesta Open Data Challenge Series Handbook

To run a successful competition, you might wish to consider the following points and generate appropriate documentation.

- Competition Call – Create a description of the ‘event’ and the format. Have you got mentors in mind? What frequently asked questions are likely?

- Look at the data sets you have; are they suitable?

- How are you going to give people access to your data? You might want to produce videos describing the data. You will need to create a licence for your data; you could consider a creative commons licence.

- Who is going to judge your competition? You will need a panel of experts, some of them external to your organisation.

- How are you going to award the winners? Will you hold an event, and who is going to organise it? Is there an opportunity for a demo at a conference or other event?

- How will you publicise the competition? Can you reach parties that may be interested, perhaps through connected organisations, email lists, Twitter, Facebook, etc.? Have you got an organisational website that can carry details of the competition?

- How will you support the competitors? WeObserve set up a Slack channel that all competitors were asked to join. Mentoring was carried out on Slack and through video calls.

- The WeObserve ODC ran a webinar about the data which was publicised in a similar way to the competition, and this was used to draw competitors in.

- Will you create a competition packet for the competitors with an FAQ and details of how they should enter the competition and how exactly what they need to do to satisfy the entry requirements? WeObserve required a code and a 5-minute video explaining the concept.

An Open Data Challenge was publicised on the WeObserve website, but more importantly, through social media and personal communications with people likely to take part. The challenge was simple: take the data from one or more of the Citizen Observatories and combine it with other data to create a new and possibly commercialised service.

Video: Gulsen Otcu discusses the HI-TERRA project

Establishing a modular system architecture that is connected directly with the processes of end-user organisations is another way to facilitate the sustainability of the Citizen Observatory after the funding period. The underpinning mission is to make Citizen Observatory outputs easily replicable and scalable, while at the same time generating economic value and social capital. This is the approach realised by the Scent Citizen Observatory, which introduces a flood management and monitoring service relying on citizen-generated data while being directly exploited by relevant end-users

Lessons learned from the WeObserve Open Data Challenge

The WeObserve team learned some valuable lessons from the Open Data Challenge, most importantly the need to mentor the teams during the competition. We found that the teams with strong mentoring produced the most viable proposals and projects. Not all teams had the experience to produce a product, but nevertheless they could contribute useful ideas. A team brokering exercise could have helped in that situation. Not surprisingly, the exercise produced some unexpected uses of the data, such as food energy calculators for farmers in Nigeria. You never know how external people will be able to use your data! All entries to the competition were open source, so that others could learn from the experience of those taking part.

The competition attracted 44 teams. Nine final entrants provided all the material requested, including details of the project and a short video describing what the team had decided to do. These entries were judged by a panel of citizen science experts, and two were selected to spend 4 months creating a final demonstration project that was presented at the ECSA Berlin conference.

![]()